Якорная проблема и как ее решить

Автор Лэнс Робертс через RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

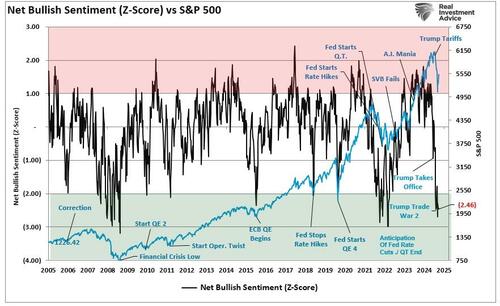

Рыночная перспектива имеет важное значение для предотвращения ошибок инвестирования. Средства массовой информации постоянно проталкивают "Рынки в беспорядкахНеудивительно, что настроения инвесторов в последнее время достигли самого низкого уровня со времен финансового кризиса. Следующий график является z-баллом совокупного индекса настроений розничных и профессиональных инвесторов.

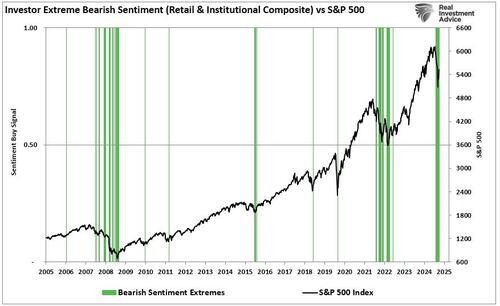

Примечательно, что мы находимся на одном из самых длинных участков более экстремальных медвежьих настроений за пределами структурных медвежьих рынков. (Читать) «Смертельные кресты и рыночные дно» Для более подробной информации и объяснения разницы между коррекцией, вызванной событиями, и структурными медвежьими рынками.

Конечно, учитывая недавнее падение рынка и всплеск "медвежий" Нарративы, основанные на СМИ, неудивительно, что медвежьи настроения выросли. Именно здесь инвесторы начинают совершать ошибки в процессе инвестирования.

Как уже отмечалось, мы находимся в одном из самых длительных периодов медвежьих настроений за пределами структурного медвежьего рынка. Разница между коррекцией, вызванной событиями, и структурными медвежьими рынками имеет решающее значение для понимания. Тем не менее, крайне негативные настроения и позиционирование инвесторов являются признаками конца коррекций и медвежьих рынков. В смысле:

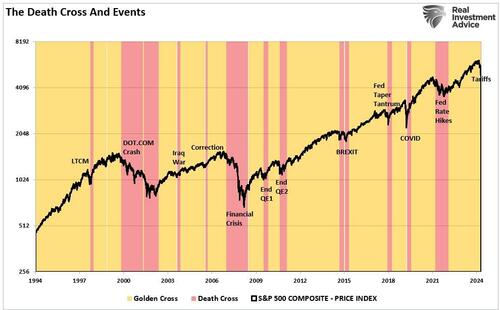

Другими словами, исторически говоря, крест смерти чаще всего является потенциальным противоположным показателем. Разница между тем, является ли «перекресток смерти» краткосрочным корректирующим процессом или большим снижением «медвежьего рынка», зависит главным образом от того, является ли причина снижения рынка «управляемой событиями» или «структурной». Этот контекст важен при рассмотрении текущего спада и запуска «креста смерти». На приведенной ниже диаграмме показана разница в длине «управляемых событиями» и «структурных» исправлений, означающих запуск «креста смерти». Периоды dot.com и финансового кризиса были структурными событиями, поскольку значительные корпоративные сбои и дислокации кредитного рынка произошли на фоне глубоких экономических сокращений. Однако, помимо этих двух значительных структурных воздействий, все другие «события» были недолгими, и рынки вскоре восстановились. "

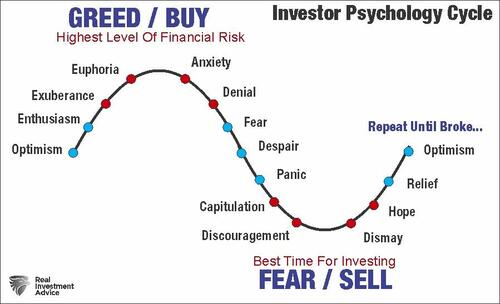

Это связано с тем, что, когда настроения наиболее медвежьи, а рынки вызывают долгосрочные сигналы о продаже, большая часть продаж уже исчерпана. Тем не менее, теперь, когда мы постоянно связаны с финансовыми средствами массовой информации, мы наводнены заголовками, предназначенными для того, чтобы получить прибыль. "клики" Больше, чем реальные новости. «Резолюции инвесторов на 2025 год» Психология инвестора является наиболее важным фактором неудачи инвестирования с течением времени. Этот цикл человеческих эмоций постоянно повторяется через инвестиционные циклы.

В то время как многие поведенческие предубеждения значительно негативно влияют на результаты инвесторов, от стадирования до предотвращения потерь до предвзятости подтверждения. "заклинание"Это один из самых важных.

Связанная проблема

«Привязка — это эвристика, раскрываемая поведенческими финансами, которая описывает подсознательное использование нерелевантной информации, такой как цена покупки ценной бумаги, в качестве фиксированной контрольной точки (или якоря) для принятия последующих решений об этой безопасности». Инвестопедия

"Заклинание" Также известный как «Ловушка относительности» Это тенденция сравнивать нашу текущую ситуацию в рамках нашего ограниченного опыта. Например, я готов поспорить, что вы можете точно сказать мне, за что вы заплатили за свой первый дом и за что вы в конечном итоге продали его. Не могли бы вы рассказать мне, сколько вы заплатили за свой первый мыльный батончик, гамбургер или пару туфель? Наверное, нет.

Причина в том, что покупка дома была важным событием в жизни. Поэтому мы придаем этому событию особое значение и запоминаем его живо. Если между покупкой и продажей дома был выигрыш, это было положительное событие, и поэтому мы предполагаем, что следующая покупка дома будет иметь аналогичный результат. Мы психологически "привязанный" На этом мероприятии мы будем основывать наши будущие решения на очень ограниченных данных.

Сегодня финансовые СМИ обучают инвесторов "якорь" к определенной точке рынка. Именно поэтому инвесторы последовательно измеряют показатели по отношению к рынку с 1 января по 31 декабря. Или, что еще хуже, мы измеряем производительность с пика аванса. Например:

- Рынок вырос на 140% по сравнению с минимумами марта 2020 года.

- Рынок упал на 10% по сравнению с пиком 2025 года.

- Рынок упал на 6% за год.

Проблема в том, что большинство инвесторов не купили дно 2020 года или не продали пик 2022 года. Однако одной из наиболее значимых форм крепления является портфель "высокие отметки воды. "Высокая отметка воды - это пиковая стоимость портфеля инвестора в течение определенного периода времени. Например, на пике рынка в 2025 году инвестор имел портфель стоимостью 1 000 000 долларов. Во время недавней коррекции на рынке стоимость портфеля снизилась до 950 000 долларов. Несмотря на то, что убыток в 50 000 долларов является значительным и, безусловно, касается этого инвестора, он должен быть помещен в контекст того, что происходит на рынках.

- Во-первых, перед коррекцией, которая началась в феврале, рынок вырос почти на 5%. Таким образом, наш примерный инвестор начал год с стоимости портфеля около 960 000 долларов США, которая выросла до 1 000 000 долларов США.

- Во-вторых, хотя снижение на 50 000 долларов является значительным, инвестор «прикреплен» к высокой отметке портфеля.

- Как отмечалось выше, за год рынок снизился на 6%, но инвестор находится примерно на том же уровне, что и в начале этого года.

- Другими словами, доходность портфеля составляет примерно потерю 1% по сравнению с падением рынка на 6%.

Да, снижение на 50 000 долларов является значительным, но это "якорь" Точки дают мало перспектив для среднего инвестора относительно их относительного положения к их финансовым целям. Однако эти "Якоря", привязаны к постоянным обновлениям в средствах массовой информации, подпитывают наши эмоциональные процессы принятия решений "жадность" или "Страх".

Давайте посмотрим на пример:

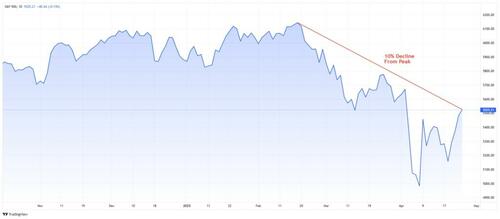

По состоянию на конец пятницы рынок упал на 10% от своего исторического максимума.

Как мы предупреждали несколько раз в 2024 году и в начале этого года, когда в конце концов наступит 10%-ная коррекция, это будет означать, что в конце концов произойдет коррекция. «чувствовать» Хуже, чем было из-за длительного периода низкой волатильности.

Да, это ужасно. Инвесторы сейчас сосредоточены на этом. "отметка высокой воды. "

Но это цель маркетинговой машины Уолл-стрит. Заставить вас сосредоточиться на текущих прибылях или убытках создает «Чувство срочности» Чтобы ты что-то сделал. Почему?

«Деньги в движении создают сборы и доходы для Уолл-стрит. "

Поэтому подталкивать вас к действиям не обязательно «Прибыльный» Для вас, но это выгодно для Уолл-стрит.

Изменение точки якоря

Чтобы уменьшить ваш «Кнопка эмоционального действия» Отойдите назад и измените свой "якорь" точка.

Если ваш портфель упал на 10% по сравнению с недавним пиком, задайте себе два вопроса:

- Я теряю деньги? Или

- Соответствует ли мой портфель моим инвестиционным целям?

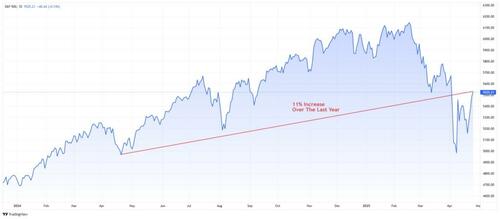

Если моя цель состоит в том, чтобы средняя годовая доходность составляла 6%, то где я сегодня относительно этой цели? Вопрос об использовании знак "высокой воды" как "якорь" психологически перезагружается, чтобы измерить нашу производительность с этого уровня. Поэтому мы должны оглянуться назад на то, где мы были в течение года. Если наша цель составляла 6% в год, то мы почти удвоили эту цель за последние 12 месяцев. Внезапно недавнее снижение не кажется столь значительным.

Однако предположим, что инвестору не повезло купить пик рынка до начала пандемии. Несмотря на закрытие пандемии, рост инфляции, опасения рецессии, войны между Россией и Украиной и все негативные заголовки, портфель по-прежнему на 63% выше. Другими словами, доходность портфеля составляет примерно 12% в год, что вдвое больше, чем требуется для достижения необходимых финансовых целей.

Дело в том, что там, где вы выбираете "якорь" Ваш анализ значительно повлияет на вашу эмоциональную психологию при управлении вашими деньгами.

Да, в этом году было много волатильности, но если я "якорь" На мой взгляд, в долгосрочной перспективе недавняя волатильность вызывает гораздо меньше беспокойства.

Рыночная перспектива очень важна.

Придерживайтесь своего процесса

Означает ли это, что вы не должны обращать внимание на свои деньги или принимать меры, когда что-то идет не так? Конечно, нет.

С помощью СМИ, подпитывающих наши страхи 24/7, от «Страх пропустить» то «Страх потерять все» Трудно не позволить нашим эмоциям стать лучше. Однако, "заклинание" Наша рыночная перспектива по сравнению с предыдущей ценой в долларах усугубляет наши хрупкие эмоциональные состояния.

В этом «Тепло момента», Легко увязнуть в эмоциональном притяжении рынков и изменениях оценки портфеля. В прошлые выходные #BullBearReport Обсудил требование быть больше похожим на доктора Спока из Star Trek при управлении своими деньгами.

"Если я спрошу вас, каков риск инвестирования, вы ответите на риск потери денег.

Но на самом деле есть Два риска В инвестировании: Одна из них — потерять деньги, а другая — упустить возможность. Вы можете устранить любой из них, но вы не можете устранить оба одновременно. Так что вопрос в том, как вы собираетесь позиционировать себя против этих двух рисков: прямо посередине, более агрессивно или более оборонительно.

Как избежать попадания в ловушку дьявола? Я занимаюсь этим бизнесом уже более сорока пяти лет, поэтому у меня большой опыт.

Кроме того, я не очень эмоциональный человек. На самом деле, почти все великие инвесторы, которых я знаю, неэмоциональны. Если вы эмоциональны, то вы будете покупать на вершине, когда все эйфоричны и цены высоки. Кроме того, вы будете продавать на дне, когда все находятся в депрессии, а цены низкие. Вы будете, как и все остальные, и всегда будете делать неправильные вещи в крайности. " - Говард Маркс

Мы все делаем «Плохой выбор» Нам нужны рекомендации, чтобы сохранить нашу рыночную перспективу.

Значительный контингент инвесторов и консультантов никогда не сталкивался с реальным медвежьим рынком.. После десятилетнего бычьего рыночного цикла, подпитываемого ликвидностью центрального банка, мейнстрим-анализ считает, что рынки могут только расти. Нас всегда беспокоило довольно бесцеремонное отношение к риску, которое пропагандируют СМИ.

«Конечно, в конечном итоге произойдет коррекция, но это лишь часть сделки. "

То, что теряется во время бычьих циклов и всегда обнаруживается наиболее жестоко, — это опустошение, вызванное богатством во время неизбежного спада.

Поэтому важно следовать своей инвестиционной дисциплине. Если у вас нет процесса, вот рекомендации, которым мы следуем во время жестких рынков.

7 правил, которым нужно следовать

- Двигайся медленно. Не стоит торопиться с кардинальными изменениями. Делать что-либо в момент «паники», как правило, неправильно.

- Если у вас избыточный вес, не пытайтесь полностью адаптировать свой портфель к целевому распределению за один ход. Опять же, после больших спадов люди чувствуют, что они должны что-то делать. Логично подумайте над тем, где вы хотите быть, и используйте ралли, чтобы приспособиться к этому уровню.

- Начните с продажи отстающих и проигравших. Эти позиции затягивались по мере роста рынка, и они лидировали на пути вниз.

- Если вам нужно подверженность риску, добавьте сектора или позиции, выполняющие или превосходящие более широкий рынок.

- Переместить уровни «стоп-лосс» до последних минимумов для каждой позиции. Управление портфелем без уровней «стоп-лосс» — это как вождение с закрытыми глазами.

- Будьте готовы продать акции и снизить общий портфельный риск. Вы будете продавать много позиций в убыток просто потому, что вы переплатили за них. Продажа в убыток не делает вас неудачником. Это просто означает, что ты совершил ошибку. Продайте его и продолжайте управлять своим портфелем. Не каждая сделка всегда будет выигрышной. Но если вы проиграете, вы станете проигравшим. Капитал и возможности.

- Если все это не имеет смысла для вас, пожалуйста, подумайте о найме кого-то. Управляйте своим портфелем для вас. Это будет стоить дополнительных расходов в долгосрочной перспективе.

Держите свою рыночную перспективу под контролем, избегайте закрепления и сосредоточьтесь на своих инвестиционных целях, а не на волатильности рынка.

Тайлер Дерден

Фри, 05/23/2025 - 10:25